Last week, undergraduate philosophers from across North America made the pilgrimage to Princeton for the first annual undergraduate philosophy conference held as a partnership between Princeton University and Rutgers University.

The keynote of the event was a keynote conversation between Stephen Stich of Rutgers University and Michael Smith of Princeton University. They presented their take on the inadmissibility and indispensability of intuitions in philosophical reasoning, respectively. The conference was organized by two Seniors in undergraduate philosophy, Max Siegel of Princeton and Jimmy Goodrich of Rutgers. For my small part, I created the website, which you can find here.

What Happens at Philosophy Conferences?

Philosophy is a field which is practiced in many different ways and places: Aristotle’s famous Lyceum was a grove and gymnasium, Sartre and Camus preferred to hang out at coffee shops like Cafe de Flore, and Nietzsche liked thinking on long walks through wilderness. What are professional philosophers up to now? How do you even practice philosophy?

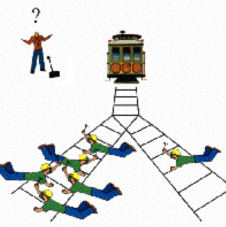

In the famous Trolley Problem thought experiment we are presented with two choices. Let the trolley continue and kill 5, or pull the switch and to kill 1. Where do your intuitions point?

Philosophy doesn’t have the kind of evidence and mathematics people are familiar with in the physical sciences. Instead, we look at the nature of concepts and logic, and we manipulate our intuitions in order to study these things. Roughly, what this translates into at philosophy conferences is that presentations are given which reflect a philosopher’s latest research, a formal argument for a view or its rejection.

For example, Liz Jackson of Kansas State University, one of the undergraduate presenters at the conference, argued that a given view about the connection between blameworthiness and belief was inadequate, and she offered her own fix for the inadequacy. The way this worked was she crafted a counterexample to the existing view about the link between belief and blameworthiness, which was both supported by our intuitions and by her motivating reasons to reject the view. Her solution, she argued, was more consistent with our strongest and more common intuitions.

Another activity that happens at philosophy conferences is perhaps, if I may, a bit more exciting than presentations: debate! It happens quite a bit in the public and private spheres, on TV and Facebook and in court. Philosophers are no different. At PRUPC the keynote was a debate between Stephen Stich, presenting his case against the use of intuitions in philosophy, with Michael Smith, presenting his case for the use of intuitions in philosophy.

Let’s look at that debate.

What’s the Debate about Philosophical Intuitions?

Philosophers will often use wild hypotheticals to appeal to our intuitions about a topic: for instance, the trolley cases in ethics or the Gettier cases in epistemology. Intuitionism is, roughly, the view that our intuitions about a domain are useful or true or justified or similar, with most forms of Intuitionism being a combination of these. For instance, moral intuitionism is a view about the epistemology of morality, or the study how we come to know about ethics. It holds that when we intuit that some action is wrong or perhaps that some end is valuable, we are at least prima facie justified in believing it or asserting it. Intuitionist views don’t claim that every intuition is correct, but more reasonably that if we carefully consider, compare, and systematize our intuitions, then we can get the truth.

Professor Stephen Stich presented his argument against the use of intuitions in philosophy on grounds that intuitions about the same cases differ based on many effects that should have nothing to do with the truth. For instance, some of his work, among many others, shows that if we change the order of the presentation of various trolley cases, the respondents will change their intuitions. Furthermore, respondents from different cultures and ethnicities had different intuitions about different cases in ethics, philosophy of mind, epistemology, and other fields. For example, east Asian culture were more likely than to ascribe knowledge in Gettier cases than others polled. Of course, the order we hear about the cases or what culture we hail from should not matter if our intuitions are justified and reflect something about each case individually.

On the other side of the debate, Michael Smith defended the use of intuitions in philosophy on grounds that it can do so much for philosophical reasoning. His way of showing this began with Descartes’ cogito, covered here a few months ago. His claim was that in intuitively investigating the statement “I think therefore I am”, all major problems in philosophy could be derived.

- If you are thinking, you can posit that other people are too, and you get the problem of other minds in philosophy of mind.

- If you ‘are,’ you can ask what it is to be and what’s the nature of being, which is the role of metaphysics.

- You can think about “what should I think?” which is epistemology.

- “I am, what should I do?” is ethics, and so on.

After the two professors presented their case and responded to some questions, they both sat at the front together to discuss the topics one-to-one. For developing and eager undergraduates like myself, Jimmy, Max, and all who attended, to see these two brilliant philosophers casually discuss so exciting a topic was thrilling.

A Review of the Debate

Professor Stich’s research into the variability of intuitions is very damning for the person who wants to defend their use. It’s really important to myself and many others that philosophy is effective at the truth, in whatever way it might do so. If intuitions vary with culture or society, and we’re systematically using these intuitions to guide philosophical reasoning, then philosophy varies with culture and society. But! Truth doesn’t vary with culture or society, so how can philosophy be getting at any truth?

Professor Smith’s investigation, on the other hand, into what’s possible with intuitions appealed to the beauty of armchair philosophy that continues to motivate my studies. The way that he showed how many different questions and answers could be accessed a priori since Descartes’ unshakable pillar was ingenious and, to me, convincing.

Given it’s prevalence for millennia, isn’t the geocentric mode far more intuitive than the heliocentric? And then even less intuitive, the Big Bang and Quantum Mechanics?

Despite this, the armchair philosopher should be worried of the skepticism that results from the inadmissibility of intuitions in philosophy. But I think moving from the variability of intuitions to the utter inadmissibility of intuitions is too hasty. When something is intuitive in contexts other than philosophy, it’s taken to be a virtue, but only on first glance. It is intuitive that every even number is divisible by two, and this is a good thing for someone that makes such a claim. However, mathematicians are going to need a proof. It is unintuitive that the fundamental nature of our world has anything to do with n-dimensional strings (or akin), but sufficient evidence will move me to adopt such a belief.

I propose philosophers treat intuitions in this sense. If you are working on your theory about knowledge or mind or value and your argument uses intuition or your theory is intuitive, you should take this as good prima facie reason to adopt your view. This is going to be similarly good evidence for people that share the intuition, but be prepared, almost as a sociological fact about philosophers: someone out there will not share the intuition. And for them, we need to have prepared an argument devoid of that intuition.

What do you Think?

What do you think is the status of your own intuitions? Surely, you find it quite intuitive that “murder is wrong,””2 + 2 = 4,” or things even more basic such as the Law of Non-Contradiction? And things similarly quite counter-intuitive, like that our world rests on the back of infinitely many massive turtles.

So the question is, do you think these intuitions are sufficient evidence to conclude anything about the nature of morality, math, or the Universe? If you do, then how can you account for people with intuitions that are different? If you don’t, how to do you explain or justify our daily reliance on them? And regardless, how do you account for that persuasive and powerful feeling of truth towards intuitive claims?

Paul Jones (Staff Writer, Rutgers University)Paul is a senior studying philosophy and computer science at Rutgers University, New Brunswick. Transferring in the Spring of 2012, Paul earned an Associates in Liberal Arts from Mercer County Community College. An active member of the Rutgers undergraduate philosophy community, he holds leadership positions in the Philosophy Club,Undergraduate Journal, and Philosophy Honors Society. He has spent the last two summers working in research and development for Local Wisdom, Inc. of Princeton Junction, developing their WeatherWise and Photomash applications on Mac, iOS, and Android.

Pingback: Experimental Moral Philosophy | Episyllogism·

Pingback: Philosophy’s Not Dead: Wave Functions, Breakfast Cereal, & Philosophy of Physics | Applied Sentience·

Pingback: Philosophy's Not Dead - Sudophilosophical·