By Naduah Wheeler

Humanist Service Corps Volunteer

I’m bipolar. There’s a lot of debate about whether to say “I am bipolar” or “I have bipolar disorder”, but the way I perceive the world is constantly processed through my disordered brain, making that distinction essentially irrelevant for me. The way I perceive the world, every interaction, and each conversation is filtered through by bipolar and avoidant personality disorder riddled brain, making my mental disorders integral to who I am as a person. I have never, nor will I ever experience the world without these filters. I will never know what it is like to be neurotypical or to have a conversation without internally fighting lion-battling level fear. But that’s okay.

Oddly, I’ve never felt particularly limited with mental disorders. They’ve irreversibly changed my life and I have the scars (both physically and mentally) to prove it, but I still always felt like I could do anything I wanted to (and not just when hypomanic). That’s why the first time I faced social stigma because of my bipolar disorder, I was completely taken aback. Shortly after receiving my official diagnosis (years after the avoidant personality disorder diagnosis), I was preparing to study abroad in Greece. As part of my preparation, I had to see the travel nurse at the university health clinic to make sure I was healthy and had the vaccinations I needed. The nurse flipped through my chart, initially asking me routine questions, until she saw the bipolar disorder diagnosis. Her lips pursed. “Oh. You’re bipolar. Well that’s not ideal.”

It was at this point that my own opinion became irrelevant. She asked if my psychologist knew I was planning to study abroad and if she had approved it. She never asked how I was feeling about it, if I thought I would be okay, what I had done to prepare for the challenges of travel. Instead, she was just concerned if I had been approved by a third-party. I remember leaving almost in tears to get the required vaccines. After receiving the vaccines and preparing to leave, the nurse noticed the bipolar note and quipped, “stay healthy… and sane” and laughed while I awkwardly gathered my things and shuffled out of the health centre.

For the first time, I felt restricted by my brain. It became clear that I was different and not only that I was different, but that there was something wrong with that difference. I learned that along with the relief, treatment, and emotional stability that came with finally being diagnosed came stigma, prejudice, and perceived limitations. In the States, when you’re bipolar people tend to assume you’re violent, crazy, aggressive, incapable of a normal life. Any mental disorder often carries with it stigmas of incompetence, aggression, and weakness. Despite these assumptions however, people with mental disorders are significantly more likely to be recipients of violence than perpetrators. If we, as a “developed” nation with relatively easy access to good healthcare continue to have significantly harmful perceptions of mental disorders and the people who suffer from them, then I wondered, what do mental disorders look like in less developed countries? In countries with little to no access to mental healthcare? In countries that don’t even recognize mental disorders as illnesses?

I quickly found out that the stigma and prejudice I faced at least acknowledged that mental disorders exist. People’s negative responses often required the recognition that there was a problem. Coming to Ghana, I realized that because mental disorders are so often not acknowledged and even rarely treated, the consequences are far more severe. While I may struggle with discrimination and stigma in the States, it pales in comparison to the severe violence at the heart of many witchcraft accusations linked to untreated or undiagnosed mental disorders.

Despite over 40% of the population exhibiting mental health problems, there are only three psychiatric hospitals and only 12 psychiatrists for the country of 25 million. Due to this extreme lack of resources, people with mental disorders in Ghana rarely if ever get the assistance they need, particularly in more rural areas like the Northern Region, which already has significantly lower access to physical healthcare. Untreated mental disorders have different consequences than untreated physical ailments. While of course physical problems left untreated can lead to further problems and even death, for many in Ghana, untreated mental disorders can bring about severe physical attacks or often, witchcraft accusations.

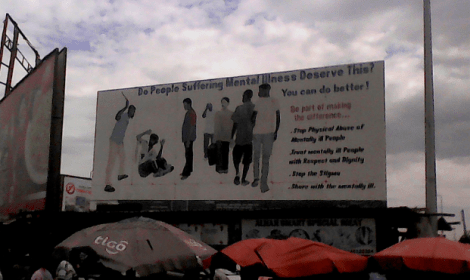

This is a billboard in the middle of Tamale, Ghana that highlights the violence mentally ill people often face. It’s a great sign that people are starting to move forward and make positive changes to help those with mental disorders.

Newspapers frequently have stories of witchcraft, linking it to mental illness. Sometimes in areas where mental illness is more well understood, some believe those with mental disorders have been cursed or hurt by a witch. In places where it is less understood, or possibly not even identified as mental illness, those who exhibit mental disorders are believed to be witches themselves. In one study, a respondent said, “People see madness, epilepsy and witchcraft as all the same. They see mental illness as the doing of witches and their curses.” Other articles recount numerous times when people have been severely injured, even set on fire, as a result of untreated mental disorders.

It’s been a wake up call. While most of the time, I don’t feel limited by my mental disorders, the moments when I do face stigma and discrimination still matter. They matter because they are a part of a global prejudice against neuroatypical people. They matter because my experiences battling my own mental disorders help connect me to a global community of people fighting their own brains and social stigma each day. My mental disorders allow me to connect with an even further marginalized part of the population we are working with. Because I often need to seek out mental health resources of my own whenever I travel, I have a motivated reason to research and learn about mental healthcare in every country, including here in Ghana, to potentially make a difference.

That’s nice, there is a brain clinic in Gh …they seem capable of dealing with mental health. I guess that’s progress

LikeLike

Pingback: I THINK THAT MY CHILD HAS A MENTAL ILLNESS, WHAT SHOULD I DO? - Reclaiming My Existance·