It was great to wear both my scientist and activist hats at the same time when I provided testimony against an anti-abortion bill in South Carolina. South Carolina introduced a bill which aimed to ban abortions at 20 weeks of pregnancy (they are currently legal until 24 weeks) on the premise that fetuses can feel pain. I have a background in neuroscience so I read up on the literature and found that the scientific consensus was that fetuses cannot feel pain. I summarized some of the main articles that had strong evidence against this bill and testified in front of subcommittees for the South Carolina House and Senate. This was a really cool experience and I’d like to share some things I learned about the intersection of science and politics.

Politicians exploit scientific uncertainty to their advantage

Before the public testimony began, one pro-life congresswoman mentioned how there is some contention over the science in this bill, but a certain amount of scientific uncertainty is okay. This troubling statement was made all too clear when my testimony filled with scientific citations against the bill was given the same consideration as testimony in support of the bill with zero scientific citations. A couple pro-life physicians (not even scientists) stated that “we all know fetuses feel pain” without any evidence and that was apparently enough to declare uncertainty about this bill. Importantly, there is always some uncertainty in any science because we cannot mathematically prove anything using the scientific method. However, scientists reach a scientific consensus based on the academic literature and they are as sure fetuses cannot feel pain as they are sure smoking is bad for you.

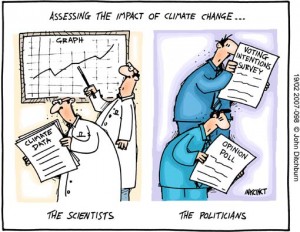

The pro-life congresswoman’s comments gave me a personal experience of how politicians will exploit scientific uncertainty to their political advantage even if it is not consistent with the scientific consensus. This tactic has been commonly used throughout political history. Another popular example involves the climate change denying politicians who support their position by using a single scientific study that conflicts with the vast majority of scientific research. The average American’s low scientific literacy also allows politicians to exploit scientific uncertainty to their advantage as well.

Politicians can capitalize on America’s low scientific literacy

How can such a blatant disregard for the scientific process exist? Politicians are very smart people and I think they simply express the values of those funding their campaign and voting for them. Others may disagree and argue that politicians don’t understand science themselves. However, the important thing is that we all play a role in this since these politicians are elected by the people. Americans have embarrassingly low scores in worldwide comparisons of scientific literacy and math and our politicians simply reflect what we value.

How can such a blatant disregard for the scientific process exist? Politicians are very smart people and I think they simply express the values of those funding their campaign and voting for them. Others may disagree and argue that politicians don’t understand science themselves. However, the important thing is that we all play a role in this since these politicians are elected by the people. Americans have embarrassingly low scores in worldwide comparisons of scientific literacy and math and our politicians simply reflect what we value.

Hopefully, as America achieves better scientific literacy, it will no longer tolerate anti-science politicians. When we understand how science works, we will elect those who listen to what science has to say. As I mentioned above, testimony without citations is weighted just as strongly as one with citations. Where are the rest of my fellow citizens calling this out? The public needs to be more active in the political process and be able to hold politicians accountable for holding anti-science views.

There are politicians who care about science!

Some may find my experience to be pessimistic and even depressing, but I’d like to end on a positive note. I testified against an anti-abortion bill in one of the most conservative states in the country, so resistance was expected. Despite this barrier, some awesome South Carolina politicians still responded very positively to my testimony! Senator Brad Hutto thanked me for my testimony and told me that I helped him answer a question about the difference between sensation vs pain. I shared my testimony with Representative James Smith and he was able to use it while debating the bill on the House floor. As I watched the House and Senate discuss the bill later on, several politicians did mention my testimony and other scientific articles as they did seem to make an honest attempt to understand the scientific consensus. The bill is currently between sessions, but there are pro-science politicians fighting for it, which is definitely encouraging!

While there are legitimate barriers between politics and science, there are also some politicians who want to understand the science, which will help break these barriers down. It would be wonderful if our society was more scientifically literate as a whole because then we would elect politicians who appreciate science and condemn the ones who do not even try to understand it. It would also be helpful if more scientists interacted with politicians and directly shared their expertise! I think if we all become more active in the political system and become more familiar with the scientific process, there will be less opportunities for politicians to exploit our lack of scientific knowledge.

I 100% agree with you. There are too many people in this nation who are scientifically illiterate or who think a single study serves as proof. (The latter problem is largely fueled by the rise of the “single study-single news article” problem in our media. How many reporters use a consensus approach or even a meta-analysis when writing their stories?) Sometimes I think the health/wellness/fitness/alternative medicine communities have the worst of it, at least on the Internet…

LikeLiked by 1 person

It would be cool to have a score board at debates for situations like you describe concerning the heavily cited testimony you gave and the “cuz I said so” testimony that followed. As Billy Madison’s principal said, “I award you no points, and may God have mercy on your soul.”

LikeLiked by 1 person