This is the second part in a series. Read Part 1 here.

On Firmer Ground

My earliest memories of Disney World aren’t so much of it as a tangible place, but of it as a tradition. My father started our annual trips when I was three, so I only know what he told me about our early years there: I was terrified of the costume characters and It’s A Small World (until I went on it, after which I demanded to go back on immediately and repeatedly). By the time I could form crystalline memories of any specific trips, the tradition itself was idiosyncratic, a myth dating back to the pre-memory of early childhood.

This ritual return lasted for nearly a decade. Even as the day-to-day realities of our own lives became more difficult—my mother’s mental illness, financial instability, my own emerging anxiety issues—Disney World remained consistent. Relatively unchanged year in and year out, it began to function as an idealization, the “ought” in J.Z. Smith’s theory of ritual contrasted with the “is” of our daily lives.

This ritual return lasted for nearly a decade. Even as the day-to-day realities of our own lives became more difficult—my mother’s mental illness, financial instability, my own emerging anxiety issues—Disney World remained consistent. Relatively unchanged year in and year out, it began to function as an idealization, the “ought” in J.Z. Smith’s theory of ritual contrasted with the “is” of our daily lives.

But if Smith’s theory about ritual is true—that ritual is holding, in conscious tension, the way things are to the way things ought to be—then the question of how we return remains. The same might also be said of mourning. After the radical rupture of loss, how do we navigate the real work of grief: the unfathomable aftermath that is the world, forever changed?

The Contemporary

As children visiting Disney World, Kristi and I had both stayed at The Contemporary. The Contemporary is one of the most idiosyncratic resorts in the entire park: A tall, trapezoidal building with rooms dotting the sloping tower walls, an open-air atrium in the center filled with shops and restaurants, and a Monorail track running through the hotel. The rooms are meant to evoke some ideal of modern chic. Everything is decorated in neutral-tones with pops of orange and teal, balconies are furnished with plastic deck chairs, and the rooms are filled with glass accents and domed lights.

As children visiting Disney World, Kristi and I had both stayed at The Contemporary. The Contemporary is one of the most idiosyncratic resorts in the entire park: A tall, trapezoidal building with rooms dotting the sloping tower walls, an open-air atrium in the center filled with shops and restaurants, and a Monorail track running through the hotel. The rooms are meant to evoke some ideal of modern chic. Everything is decorated in neutral-tones with pops of orange and teal, balconies are furnished with plastic deck chairs, and the rooms are filled with glass accents and domed lights.

This was the place we associated with our fathers. The 70s prediction of 90s futurism was what we remembered, and where we wanted to go.

Nesting in the Rain

Kristi and I began fidgeting in our seats as our bus got close to the hotel. When the top of the building appeared over the tree line, Kristi pointed and yelled, “There it is!” A Monorail arced in and out of view. We gathered our bags minutes before the bus pulled into the parking lot. When we finally arrived, we stepped off the bus and onto salmon-colored bricks under a charcoal sky.

My typically stoic New England demeanor shattered. “We’re here!” I screamed, two octaves higher than I knew my voice could go. We jumped up and down and hugged.

As we checked into our room, we told the desk clerk the story of our fathers. She beamed. “That is just the loveliest thing I’ve ever heard,” she said, handing us our keys. “Now you girls go have fun!”

“We will!” I told her. Kristi nudged me, a reminder to ask the most pressing question of any arrival in a new place. “Oh, right,” I began. “Where can we buy wine?”

With 4 bottles of Chardonnay in hand, we made our way to our room. When we got inside, we ran around excitedly, pointing our details the other hadn’t seen yet. We jumped on the beds. We went to the balcony. Facing the Magic Kingdom, we opened a bottle of wine to toast our arrival. Despite the hurricane conditions, everything was exactly as we’d left it. A better myth of our childhoods, unchanged.

We sat on the balcony and drank without speaking, listening to the hum of the Monorail and the crescendo of rain.

On Transience

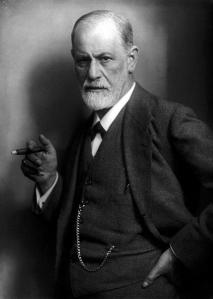

In the middle of World War I, Sigmund Freud wrote On Transience, a short meditative essay on grief and finitude. Inspired by a conversation with a poet—who lamented the impermanence of spring and the coming decay of all he beheld—Freud penned this essay as a way to press upon another possibility. “This demand for immortality is a product of our wishes too unmistakable to lay claim to reality: what is painful may nonetheless be true…What spoilt their enjoyment of beauty must have been a revolt in their minds against mourning.” For Freud, the human psyche recoils against change because change produces iterations of mourning, and reminds us of what we have lost. He theorized that the “libido clings to its objects and will not renounce those that are lost even when a substitute lies ready to hand. Such, then, is mourning.”

In the middle of World War I, Sigmund Freud wrote On Transience, a short meditative essay on grief and finitude. Inspired by a conversation with a poet—who lamented the impermanence of spring and the coming decay of all he beheld—Freud penned this essay as a way to press upon another possibility. “This demand for immortality is a product of our wishes too unmistakable to lay claim to reality: what is painful may nonetheless be true…What spoilt their enjoyment of beauty must have been a revolt in their minds against mourning.” For Freud, the human psyche recoils against change because change produces iterations of mourning, and reminds us of what we have lost. He theorized that the “libido clings to its objects and will not renounce those that are lost even when a substitute lies ready to hand. Such, then, is mourning.”

While Freud posits a metaphysical movement out of grief in his essay, he doesn’t attend to the early navigation, to how we make sense of the world, unchanged as a whole, while our lives have dramatically ruptured. It is this space that I find most compelling, because it seems to occupy the penumbra between the end of the ritual and the beginning of what Freud calls mourning’s “spontaneous end.”

Regardless of religious affiliation, what constitutes this process is a kind of psychic cartography, a re-mapping of relational dynamics from external to internal, the assimilation of what we’ve lost into dialectic memory, into narrative. For those who follow a religious path, this assimilation is inextricably bound in certain conventions of public mourning rituals. For those of us who identify as atheist, agnostic, and humanist, the assimilation is often the product of a different kind of ritual, a patchwork striving for authenticity.

This authenticity is consistent to all acts of mourning. Celebrations of lives need to be reflective of why those lives mattered. The shock of the absence must be attended to in a way that not only honors the person who has been lost, but also the loss itself, in order to name the space in which we must relearn to navigate the world in the unfathomable absence.

The Image They Remember

Disney World as an entity is a strange and sublime instance of transience. Though it has transformed considerably since its opening in 1971, in another sense, the park rarely changes. More aptly, Disney is decidedly careful about how they implement such changes. The organization knows full well how attached visitors become to not only beloved attractions and designs, but to the little touches that made the resort a world apart. It is this attachment that the organization carefully contends with as it renovates parks, refurbishes rides, and expands. Everyone who loves Disney World wants to return to the image of the park that they remember.

Kristi and I had specific images we wanted replayed, vestiges that we needed in order to root ourselves into something more stable in the aftermath of our losses. And most importantly, we needed a way to locate our fathers, a way to place them and their memories and their histories in tangibility so that we could begin the process of internalization that is the grueling work of mourning.

A Brief Interlude on Very Responsible Decision-Making

Our first night at the hotel was fittingly raucous. Kristi and I invented a game called “Drink Around the Monorail,” whose rules should be evident based on the title. We stumbled back to the room, and proceeded to drink more wine as we got ready for our sit-down dinner at the California Grill, one of Disney’s upscale restaurants that was, fortunately, in our hotel. At the restaurant, the hostess gave us a buzzer that was supposed to light up once our table was ready. We took tipsy glamor shots in the lounge. After waiting for over an hour, we discovered that our buzzer was broken. As an apology for the wait, we got an upgraded table and a complimentary bottle of wine.

Our first night at the hotel was fittingly raucous. Kristi and I invented a game called “Drink Around the Monorail,” whose rules should be evident based on the title. We stumbled back to the room, and proceeded to drink more wine as we got ready for our sit-down dinner at the California Grill, one of Disney’s upscale restaurants that was, fortunately, in our hotel. At the restaurant, the hostess gave us a buzzer that was supposed to light up once our table was ready. We took tipsy glamor shots in the lounge. After waiting for over an hour, we discovered that our buzzer was broken. As an apology for the wait, we got an upgraded table and a complimentary bottle of wine.

How we managed to wake up the next day without hangovers, I will never know.

Coming Home to Empty Rooms

Purists that we were, Kristi and I decided that going to the Magic Kingdom first was non-negotiable. We took the Monorail from the hotel, and arrived in the park on an overcast day. The tail-end of the hurricane—scattered downpours and cool gray weather—meant that the park was nearly empty. With no lines, we darted back and forth across the park, jumping on every ride that struck us. And on every ride, we instinctively shared stories about our families, our fathers, and our own childhoods.

We walked right onto “It’s A Small World.” Animatronic dolls—the cultural stereotypes portrayed so simplistically they struck me as uneasy and offensive—welcomed us to the world we already lived in. “You know,” I said as the boat began to enter the tunnel, “When I was little, I was scared of this ride. I didn’t like the fact that it went into a dark place. When my dad finally convinced me to go on it, I loved it so much we had to ride it seven more times that day.”

Kristi put her arm around me as our boat swayed. Smiling dolls in toy hot air balloons rose and fell along a vertical axis. She didn’t say anything, but she didn’t need to. The rediscovery of the unchanged in contrast to the absences was enough to make both of us silent.

Every ride we went on was a story. We shared memories about specific attractions. Kristi showed me photos of her mother standing in front of Thunder Mountain, and we recreated the picture with her in her mother’s place. I told Kristi about the time my father made me walk on tip-toes so I would pass the height requirement and be allowed on the roller coaster. And throughout the day, we instinctively knew our way around, a latent cartography of a place we knew by muscle memory and idealization.

The park, awash in silver rain, was undoubtedly the same place we remembered. But as we pointed out the small changes—a new restaurant here, a new sign there—we began to root ourselves back into the world as it is. Acknowledging the differences, recognizing the ought as the unattainable ideal that we still strive for, is always the true closing of every ritual.

Late in the day, exhausted from hours of walking, we decided to go on the People Mover, an open-air tram ride that snakes around Tomorrow Land. Though not a thrill ride, it’s a beloved-but-antiquated aspect of the park, both because it’s one of the original rides from the 70s, and also because it’s an easy way to sit for an extended period of time.

Late in the day, exhausted from hours of walking, we decided to go on the People Mover, an open-air tram ride that snakes around Tomorrow Land. Though not a thrill ride, it’s a beloved-but-antiquated aspect of the park, both because it’s one of the original rides from the 70s, and also because it’s an easy way to sit for an extended period of time.

Alone in our tram, Kristi and I listened to the familiar automated tour, the soothing voice that happily told us to look left and right to see things we already knew were there. “It’s amazing,” Kristi began. “This hasn’t changed a bit…” Then, the familiar quiet.

The ride hadn’t changed, but being there, in the “ought” of impermanence, was a mere respite from the world as it was. And even in the ideal, we still had to contend with the realities we carried with us.

The space of unknowing between the closing of the ritual of contrasts and the slow work of grief is nebulous, but necessary. In the aftermath of loss, we all need a space where we can voice the uncertainty, the unfathomable sprawl of the world as it is, forever changed. I think this, more than anything, was the authenticity Kristi and I wanted: A space where we could say “nothing has changed,” even though everything, as always, had.

As the tram snaked along the track leading to the exit, Kristi wiped her eyes. I squeezed her hand.

“Back to the hotel?” I asked.

She nodded. “We have to be at dinner by 7, anyway.”

Joining “Is” and “Ought”

In permanence we find the siren song of the ideal. If authenticity is paramount, then I wanted the authenticity to be firmly there, in the improbable place that was both an idealization and the expanse of life without my father. I wanted to remember, but I also wanted to see this place without him, fully conscious of his absence.

At the end of On Transience, Freud wrote “I believe that those who think thus, and seem ready to make a permanent renunciation because what was precious has proved to not be lasting, are simply in a state of mourning for what is lost. Mourning, as we know, however painful it may be, comes to a spontaneous end…We shall build up again all that war has destroyed, and perhaps on firmer ground and more lastingly than before.”

At the end of On Transience, Freud wrote “I believe that those who think thus, and seem ready to make a permanent renunciation because what was precious has proved to not be lasting, are simply in a state of mourning for what is lost. Mourning, as we know, however painful it may be, comes to a spontaneous end…We shall build up again all that war has destroyed, and perhaps on firmer ground and more lastingly than before.”

What Freud considered a “spontaneous end,” is something much more deliberate: It is the reunification of the “is” and the “ought” that separate during ritual, the internalization of what was lost so it becomes a part of ourselves. And, ultimately, it is through this that we learn to re-enter the world, forever changed, forever changing.

[1] Jonathan Z. Smith, To Take Place: Toward Theory in Ritual (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987) 110.

[2] Ibid, 109.

Meghan Guidry (Harvard University)Meghan is a Masters of Divinity candidate at Harvard Divinity School, where she studies bioethics, humanist philosophy, end-of-life care, and health policy. Her research focuses on the disconnection between ethics and technologies, assisted suicide, and other cheery subjects. Her interests include creative writing, swimming, language philosophy, medical sociology, and coffee. You can check out her books at Empty City Press, find her on Facebook, and follow her on Twitter @MeghanGuidry1.

Pingback: A Place on Earth: Ritual, Grief, & Mourning as an Atheist, Part 1 | Applied Sentience·

Absolutely beautiful!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much for reading, Azzad! I’m glad you enjoyed it, and I hope you’ll check out the third part of the series (which should be up in a few days). 🙂

LikeLike

Absolutely

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much Tarfaaaron!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Beautifully written from the images contained in your heart and an everlasting reminder of those placed there by your father, remember that no matter what happens in your mourning or absence, nothing can take away those memories and prevent you from moments of bliss with that special person who was you dad. I am just starting out on this blogging path and it is to heart issues I turn. May you find comfort in treasured memories.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much, Ian, and thank you for your kind words and wishes. Writing about this experience, and having an opportunity to revisit these memories in a way that’s both intentional and focused, has been a wonderful source of comfort and a reminder of the importance of staying rooted to the parts of our lives that provide us with the sustenance we need to stay rooted and compassionate. I hope you’ll read the next part of the series, which should be out in a few days, and thank you again!

LikeLike

Hello Meghan,

Very interesting piece. Your trip, your friend and your writing all seem to have helped you through the grieving process. It’s such an important thing to do, and I’m glad you wrote about it to help others.

Just one quest… As an atheist, why an M.Div.? Mine was hard enough as a Christian.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much, Appliedfaithorg! I really appreciate your thoughtful comment, and your question. I chose the MDiv because my academic work focuses on end-of-life care issues (particularly bioethics in applied settings). The MDiv allowed me to study bioethical literature, philosophy, and the sacred texts of other traditions while also exploring the practical challenges of delivering quality end-of-life care in contemporary medicine. The MDiv’s focus on combining research and practice really appealed to me, which is why I ultimately chose that as my program. It’s been a wonderful experience, and I’m especially grateful to have had the chance to study how different traditions approach death and dying, and how those approaches manifest in contemporary medical settings. I hope you’ll keep reading the series, and thanks again for commenting!

LikeLiked by 1 person

The freedom to work throughout Christian ministry led me to get my M.Div., and it sounds like you’ve found a similar freedom and applicability. It will be my pleasure to check in on your blog. Godspeed on your academic journey. I hope you post about your graduation.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It does sound like we’ve found similar paths in this program. I hope your journey has been fulfilling and satisfying, and I’ll try to post about my graduation. Hopefully I can get a picture of myself in that cap that I don’t hate 😉

LikeLiked by 1 person

Loved these posts. As a recent widow and Disney lover I have lived the “everything here is the same” and yet in my heart it isn’t silence. I made my first trip back to Disneyland without Dave earlier this year, and people kept telling me he would be there. I am not sure about that, I haven’t decided about what happens “after.” I am somewhat envious of those who “know for sure” there either is or isn’t something after, those of us who don’t have ritual or surety have an interesting road to be sure.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much for sharing this, W, and for sharing your story. I’m so sorry for your loss, and I hope that your trip provided some form of comfort and solace, even if Dave’s “being there” wasn’t evident. I agree with what you said about how the path forward is interesting for those of us who don’t have that certainty of an after. It’s something I wish I had as well, and something that I found I missed dearly after I lost my father. I hope that you’re finding your road, and finding ways to walk this path that feel authentic to you, to Dave, and to the love you shared.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Beautiful, moving, thought provoking. Thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much, Tandi, and I’m so glad this resonated for you! I hope you’ll check out the rest of the series. Part III should be up in a few days. 🙂

LikeLike

Pingback: A Place on Earth: Ritual, Grief, & Mourning as an Atheist, Part 3 | Applied Sentience·

Pingback: A Place on Earth: Ritual, Grief, & Mourning as an Atheist, Part IV | Applied Sentience·

Pingback: A Place on Earth: Ritual, Grief, & Mourning as an Atheist, Part 5 | Applied Sentience·