We hate changing our minds.

When politicians do it, pundits call it a “flip-flop” and laugh at them. When pundits do it, other pundits laugh at them. (Except for Philip Tetlock, who welcomes them with open arms to the land of right thinking.) The appearance of several very good books about the phenomenon hasn’t even left a dent in our public discourse.

Many of you are reading this blog because you are humanists. And many of you humanists believed in a religion at some point. This means that you’ve changed your mind about something big. If so, congratulations! Changing your mind is hard.

Unfortunately, doing it once is no reason to rest on your laurels; you probably hold a variety of beliefs that you haven’t tried to question in years. That’s okay. So do I, and I’m the person writing this.

But I think it’s a shame that we don’t change our minds more often, and I’d like to explore ways that we might do a better job of updating our beliefs in response to evidence.

In this, the first of two complimentary posts, I examine the stories of two well-known people who achieved their fame in part through the expression of their beliefs. Neither is unique in the views they held or the steps they took to support those views.

However, they both did something very rare – they changed their minds, in the face of strong incentives to stay the course. I consider this an act of great moral courage, and I hope you’ll find their stories inspiring. After all, if they can change their minds, what is stopping us from doing the same?

Alan Chambers, Leader of Exodus International

Chambers took part in two homosexual relationships before undergoing therapy and later marrying Leslie.

For a time, Exodus International was the most powerful organization in the world of “conversion therapy”, which targets gay people who hope to become straight – or whose parents make that decision for them. Alan Chambers, alongside his wife Leslie, led Exodus for 11 years, serving as the public face of conversion therapy.

Just over a year ago, Alan Chambers explained in a live television special, seen by millions of people, that he was closing Exodus. He apologized to the gay people whose lives Exodus had impacted, describing his contrition as “unequivocal, unconditional”:

I am sorry I didn’t stand up to people publicly ‘on my side’ who called you names like sodomite—or worse. I am sorry that I, knowing some of you so well, failed to share publicly that the gay and lesbian people I know were every bit as capable of being amazing parents as the straight people that I know. I am sorry that when I celebrated a person coming to Christ and surrendering their sexuality to Him, I callously celebrated the end of relationships that broke your heart. I am sorry I have communicated that you and your families are less than me and mine.

The apology wasn’t a complete surprise. Chambers describes his own sexuality using the ambiguous term “Holy-sexual”, and admitted the flaws of conversion therapy in public long before the closure of Exodus. But it is still the case that his job – and the respect of millions of his fellow Christians – depended on his continued support of the pernicious practice.

And yet, he changed his mind.

Christians who swear by the benefits of conversion therapy were not very happy about this. And many fierce opponents of conversion therapy flatly declared that they wouldn’t be forgiving Chambers for his former work with Exodus. Plenty of people were happy about the shutdown, but very few became fans of the man who took steps to correct his mistake.

You can see why people don’t do this kind of thing very often.

(Note: As many have pointed out, Chambers still holds many views I consider mistaken and harmful. In this, he resembles many other leaders of all stripes — save that those leaders never bother to question their own views in public. Chambers is not an especially moral man, but his story still holds a moral lesson for those with similarly misguided beliefs.)

Patty Wetterling, Child Safety Advocate

In 1989, Patty Wetterling’s 11-year-old son was abducted by a masked man holding a gun. She never saw the boy again, though the case remains open.

In 1989, Patty Wetterling’s 11-year-old son was abducted by a masked man holding a gun. She never saw the boy again, though the case remains open.

In the face of this horrifying experience, Wetterling’s response was heroic. She founded the Jacob Wetterling Foundation to further the cause of child-safety education, and eventually succeeded in convincing Congress to pass the Jacob Wetterling Crimes Against Children Sex Offender Registration Act in their 1994 Crime Bill. For many years, she was one of the nation’s best-known advocates for what she calls “broad-based community notification laws“, which compel states to notify the public about registered sex offenders living nearby.

These laws often keep sex offenders on the register for life, making it nearly impossible for them to find work or live anything close to a normal existence. This doesn’t bother many people – after all, who wants to stand up for the rights of rapists and child molesters?

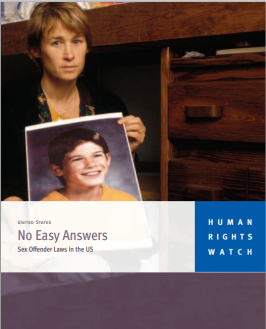

But Wetterling – whose life had put her in a position to hate sex offenders without reservation – soon began to shift her stance. In 2007, she was quoted in a report from Human Rights Watch, admitting that she’d been wrong about many of her closest convictions:

I based my support of broad-based community notification laws on my assumption that sex offenders have the highest recidivism rates of any criminal. But the high recidivism rates I assumed to be true do not exist. It has made me rethink the value of broad-based community notification laws, which operate on the assumption that most sex offenders are high-risk dangers to the community they are released into. (emphasis mine)

Around the time the report was released, Wetterling also composed an op-ed in the Sacramento Bee, titled “The Harm in Sex-Offender Laws”, explaining both her past and present beliefs with an evenhanded honesty rarely found in newspaper op-eds (or anywhere else).

Alan & Patty

Unlike Alan Chambers, Patty Wetterling does not run a public blog. It’s been many years since she spent much time in the news, and any public criticism of her new positions died down long ago. For all I know, Patty Wetterling didn’t take the same risks as Alan Chambers, who knew he’d be creating a media firestorm when he appeared on the Oprah Network.

But in some sense, she may have risked more than Chambers.

(Warning: The following paragraphs are wild speculation, and should not be construed as an accurate psychological evaluation of a real person.)

Rather than breaking ties with a social group, Wetterling chose to part with a certain view of herself, a view she’d held for many years.

While fighting for the passage of Jacob’s Law, she was, in her own mind, a moral hero, pursuing righteous justice against criminals whose existence outside of prison threatened the lives of innocent children. Many years later, she chose a harder path in life – the path of the person who sees evil, stops, and considers the rest of the story. The new Patty Wetterling admits that sex offenders aren’t especially likely to re-offend, and that current laws are likely far too harsh toward a group of people who deserve a second chance.

“These people are not monsters,” says the new Patty Wetterling. “They’re living and functioning amongst us, and we’ve got to figure out a way for them to live amongst us and not harm [anyone].”

What would the Patty Wetterling of 1990 think of the Patty Wetterling of 2007? Only Wetterling herself knows for sure. But whatever the answer, she changed her mind for the sake of a group of pariahs who – unlike gays in Evangelical communities – had mostly committed acts worthy of outcast status. She put her faith in human nature, and in the cold truth of crime statistics.

I happen to agree with Wetterling’s new beliefs. But whether or not they are wise beliefs, her decision to stand for them in public was an act of moral courage.

Next Up

In my next article, I’ll be looking at practical techniques we can use to change our minds when the evidence is against us, despite the psychological pressures pushing us to stay the course.

Stay tuned!

Aaron Gertler (Yale University)Aaron is a member of the class of 2015 at Yale University. After he graduates, he hopes to live his life in a way that makes the lives of other people significantly better, unless he gets distracted by his dream of becoming a famous DJ/novelist/crime-fighter. His interests include electronic music, applied psychology, instrumental rationality, and effective altruism. If his beliefs are inaccurate, you should tell him so as directly as possible. You can follow him on Twitter @aarongertler, and he also writes for his own blog.

Don’t you think that advocating for “changing your minds” follows a hindsight fallacy? For example, if someone changes his mind from something false to something true, we’ll all say “Wow, I really need to question my own beliefs more often and view the world more critically,” but if someone changes his mind from something true to something false, we won’t.

My point isn’t that changing your mind is a good thing. And my point isn’t that changing your mind is a bad thing. Finding truth in this world is not a result of changing your mind. (If that were true, people would keep changing their minds every generation and rejecting whatever came before them.) Finding truth is a result from careful, deliberate thinking of what is right and wrong. This COULD mean you have to change your mind.

“Changing your mind is hard.” Keeping the same beliefs for your whole life is hard, too. Figuring out which beliefs are RIGHT is the hard part.

Let’s face it. Wanting people to “change their mind more often” is fine if someone else’s beliefs are dangerous and (in some senses of the word) fundamentalist. But “changing your mind” not the right fulcrum to leverage the way you want to make the world a better place.

Unless, of course, you don’t want to change your mind 😉

LikeLiked by 1 person

It seems to me your comment is a case of mixing up intentions and actions. For instance, we will always applaud someone who gives to charity with good intentions, but lament the fact they did it if it turns out the charity is a hoax and the person just funded terrorist extremists.

Changing your mind to conform to your well researched evidence is always good. The fact of the matter after that, whether it turns out you really are right or wrong, is more or less out of our control – hence the ‘well researched’ bit. As I see it, this article is praising 1) an attitude towards one’s own beliefs, namely, that they follow evidence, and 2) the courage to change them against enormous pressures to conform. This is always praiseworthy, though sometimes might have bad, not ideal, or unintended consequences.

LikeLike

By the way (forgive me for writing so much, but this is a very interesting subject), I think a better way to look at making the world better is distance people from their beliefs (be it humanism, secularism, religion, whatever). When people don’t want to change their minds, often it is because they hold their beliefs to be a part of their identity (and who can blame them? Some people call themselves “humanists,” some call themselves “free-thinkers,” some are religious, everyone has a name and a voice). If you’re trying to persuade someone something, then, by distancing the negative effects of those beliefs/views from the person, that person feels less offended/afraid of changing his/her mind. (For example, if I say “you’re racist”, you’re much more likely to be offended than if I say “you said something that may be considered offensive by others”).

The reason I write this is because I don’t like to criticize other peoples’ ideas without bringing something else to the table.

These examples you gave were from people who were able to distance themselves from their beliefs. They also recognized they can be wrong sometimes (just like anyone).

LikeLiked by 1 person

If I may take a stab at this one too. There are a few reasons why your argument might not characterize humanism, and why humanism might still be worth identifying with even if it isn’t perfect.

First, it is a non-dogmatic worldview. Prophets, revelation, etc are replaced by a method, namely science and philosophy. Humanism is relatively unique in that it holds critical thinking and the kind of virtues I wrote about in my last comment higher than any others. Further, you may even need a community like this to consistently reaffirm your values when you have reason to rationalize them. Going solo makes it much easier to rationalize the beliefs you hold to whatever most suits your interests (instead of truth) because you don’t have a community to get a reality check from or consistently remind you of the values I wrote in my first point. As long as you choose the group and have the option to leave (no hell or karma in humanism) then it may serve to strengthen instead of weaken critically examining yourself.

Second, there are simply other benefits to belonging to worldview groups. Almost any positive psych book you read will tell you to join a church, be it fundamentalist or humanist, to live a longer and healthier life.

Lastly, to kind of sum up, every human group we will ever form stagnates and becomes resistant to changes in belief. People become sometimes violently passionate over sports. “Science advances one funeral at a time” as the saying goes. People get wrapped up in, for lack of a better word, the circle jerks within art movements. So should we also close down sports events? Or stop giving labels to academic institutions, theories, or give titles for professors? Or cease identifying artists we love or styles we paint in?

Basically I agree with your argument, but conclude we should be extra wary and not that we should throw out the baby with the bathwater.

LikeLike

Found the TED Talk I was thinking about:

LikeLike

McFoofa,

Thank you for a series of thoughtful comments! A couple of quick thoughts, typed from my desk at work:

1) I agree that “holding fast to correct beliefs, even when it’s hard” is an epistemic virtue just as important as “changing your beliefs when it is rationally correct to do so”. Both are related to the central virtue of “updating beliefs accurately in response to evidence”.

However, in my experience, when people fail to update correctly, it is more often the case that they hold on too tight to their existing views than that they change their views to a greater extent than the evidence warrants. I can imagine a person in the latter category — the stereotypical aging hippy, perhaps, who adopts new spiritual stances as easily as ze changes outfits. But I think more people are in the former category. Hence, when left to write about only one of the two mini-virtues, I chose “changing one’s mind”. But it would be worth writing about the other, too — thanks for the idea!

(You can also quickly Google “people more often overconfident than underconfident” and “confirmation bias” for more on this apparent imbalance.)

2) It certainly doesn’t do much to criticize others’ beliefs without proposing alternate hypotheses! I hope that I can go the rest of my life without making that mistake; it bothers me when I see it happen in the world. And you’re very correct that offending people won’t get us anywhere — this is a central part of the humanist ethos, as Paul mentioned.

See also this related article, one of the best I’ve ever read about how to argue in a helpful way: http://lesswrong.com/lw/o4/leave_a_line_of_retreat/

Best,

Aaron

LikeLike

Pingback: Two People Who Changed Their Minds | Alpha Gamma·

I used to look very critically at people who changed their opinion about something ‘big’. Similar to Alan Chambers’ views you mention. Example: I know people who changed their position from anti-market or pro-authoritarian to liberal and pro-market. Or vice versa.

But I believe critical assessment of your positions and believes to be a sign of certain intellectual advancement. The funny part is that as I realized that being critical to your own positions is smart, I also started to perceive these ‘converted’ individuals differently, thus changing my own positions. Logic is beautiful.

LikeLike

Pingback: How To Be Wrong: Changing Our Minds, Pt 2 | Applied Sentience·

Pingback: Why I Love Being Uncertain | Applied Sentience·