The recent persecution of atheists in Muslim-majority countries like Indonesia, Pakistan, and Bangladesh has prompted some hand-wringing and mild-mannered protests in secularist communities. Nonbelievers, as a rule, just don’t think of themselves as part of a global community of nonbelievers, or at least not enough to provoke revenge violence. As a result, atheists have largely outsourced the legal advocacy work around these cases to human rights NGOs like Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch. However, there is little that such groups can do within the existing framework of laws, and the atheist cause is simply not sexy enough to inspire reforms towards laws like in China that protect the right not to believe in religion. After all, some bloodthirsty Communist government bulldozing your grandmother’s church: this image does well to lubricate our tears. The tragically hip artist in the city café, denying God between smug sips of red eye and Nietzsche? Her human rights are acknowledged only begrudgingly, if at all.

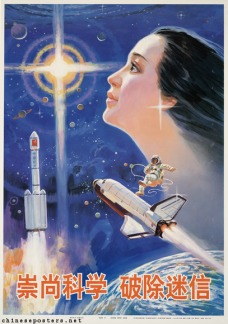

Chinese law considers both ordinary believers and atheists before organized religion. Credit: Siutou Amy, CC-by-nc-nd

But the problem is less superficial than one of marketing: it is the language of the law and the way that we frame the issue of “religious freedom” that values any religion over no religion, and which denies a space for unbelief in global civil society.

The highest appeal which non-governmental organizations can make against religious persecution is to Article 18 of the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UHDR), to which all national laws and international treaties must comply. The complete text of the article asserts that:

Everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion; this right includes freedom to change his religion or belief, and freedom, either alone or in community with others and in public or private, to manifest his religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship and observance.

Although the Declaration does not explicitly condemn atheism, neither does it protect a human being’s right to excuse himself or herself from compulsory religious practice. Consequently, when atheists fall victim to mob violence compounded by deficient legal protections, there is no international legal recourse for them.

Searching for the strongest national protection for atheists in law, no safeguards compare to that in the Constitution of China. The 1975 Constitution, which differs from the now-effective 1982 version only in concision, states that

Citizens enjoy freedom to believe in religion and freedom not to believe in religion and to propagate atheism.

In practice, to borrow an analogy from Thomas Selover, the government in China treats religious proselytization like secondhand smoke: You are allowed to smoke, as I am allowed not to smoke. But in the public square, please do not take out your cigarette, because we all enjoy the freedom to breathe clean air. For those who currently push the boundaries of religious freedom, such as the Westboro Baptist Church, this approach might seem like an essential loss of liberty. But for the rest of us, such a law only codifies the best practices of modern multicultural society, which has increasingly come to understand proselytization as aggression.

The good news is that the freedom not to be subjected to public religion does not merely confer aesthetic benefits. It also strengthens the public health, the public order, and the public education infrastructure.

1. Pro-Science Advocacy. In the 1990s, an explicit challenge to the public and indeed world health came to China in the form of a “healing cult” called the Falun Gong. Unchecked for years, the Falun Gong promoted its healing magic to millions of subscribers while discouraging devotees from consulting secular physicians. Ultimately, the group was undone by its foray into national politics in 1999, but its continued media activism and appeal outside China strikes a cautionary tale for governments that fail to intervene against dangerous pseudoscience. America’s decades-long struggle with disproportionately high rates of teenage pregnancy is no doubt related to religious opposition to contraception and abortifacents. China’s refreshing, muscular approach to disseminate pro-science propaganda could see a rapid increase in public health outcomes here.

2. Limits on International Lobbying. While the US constitution prohibits the establishment of a state religion, China’s constitution more narrowly addresses the rights of individual believers. Both approaches are well within the bounds set by the UHDR, but China places less restrictions on its government to regulate religious bodies. As a result, the largest state-supported religious organizations in China identify as “patriotic”: in effect, the Chinese Patriotic Catholic Association appoints its bishops indigenously, rather than by phoning home to Rome. These Catholic leaders pledge to uphold Chinese law, rather than to propagate the Vatican’s idea of good government (which at one point included Fascist Spain). Religious interference into politics—like the Washington state diocese’s panhandling for antigay ballot initiatives—could not happen in China. There, not only are the rights of individual believers protected, but also the rights of nonbelievers are protected, since nobody suffers the consequences of politics organized from within the pulpit.

3. Religion Becomes a Heartfelt Choice. The idea of a freedom not to believe in religion has particular implications for children, who society deems worthy of special protection. In protecting the freedom not to believe, China’s education law separates religious education from compulsory state education, while allowing for parent-to-child transmission of religious values. Far from destroying religion, many adults who already learned about world religions in state school still choose to study theology at the university and graduate level. In contrast to America, where pews remain open to all but unfilled due to dampening enthusiasm, many Chinese are excited upon reaching the age of majority to become officially inducted as Daoists, Protestants, or Buddhists. While protecting children from forced observance may ultimately reduce the ranks of the faithful, the overall quality and commitment of believers actually increases. This change should be appreciated by both religious leaders and child welfare advocates.

———-

Realistically, legal reforms to safeguard citizens’ choice of no religion will be resisted by those whose power it threatens. Individual religions set their own criteria for membership and excommunication, so to interfere with this process by making it safer to jump ship is a direct interference with the religion’s internal system of rewards and punishments. But a new kind of diversity has emerged in America that deserves respect: as of 2012, “One-fifth of the U.S. public – and a third of adults under 30 – are religiously unaffiliated today”. The lucky presence of a liberal democratic culture, as well as the absence of powerful religious fundamentalists, protects atheists and agnostics in certain areas and for now. But as our ex-Muslim brothers and sisters demonstrate, the lack of a universal right of unbelief to which all humans can appeal can prove deadly, perhaps closer to home in the not-so-distant future.

Any attempt to dismantle the tyranny of organized religion over nonbelievers will bring out the wolf-criers of “Communism!” But this time-tested hatred contains the seed of its own destruction. After all, if the Soviet Union was wrong to restrict free commerce from Monday through Sunday, then why is Bergen County, New Jersey not also wrong to restrict free commerce on the Sunday sabbath? The fundamental issue of freedom – whether it’s from the power of the state, or from the power of the church – is the same. But the lesson from China is that to decrease the unelected power of religion over healthcare, education, and politics, reforms will have to leverage the increased power of the state. The test for America is whether it can handle an expansion of the power of democracy, at the expense of our comforting, authoritarian traditions.

James Carroll (Staff Writer, Rutgers University)James Carroll is a Rutgers student studying for his B.A. in political science. He regularly geeks out over the histories of China’s borderlands, but loves nothing more than to expose the ironies and hypocrisies of “dissident” and anti-authoritarian movements. As a connoisseur of all things queer, sarcastic, and sublime, James is always ready to have his worldview challenged by his adversaries, and expects the same respect from all of his readers.

Reblogged this on World of Values, a blog of the humanistic tendency and commented:

While the government of the PRC tends to abuse the human rights of its citizens, one of the few aspects of the PRC’s state atheism which can be appreciated is the explicit constitutional protection of the freedoms to believe and not believe in any religious ideology or observance. This is not protected by most national constitutions.

LikeLike

What you euphemistically call “Limits of International Lobbying” is nothing less than a textbook case of authoritarianism or even facism in action.

How can you possibly agree with the principle of not allowing people to freely associate themselves with an organization that is based outside of their home country? Even in the darkest hour of European nationalism and “Kulturkampf”, the Catholic Church was allowed to appoint their own Bishops and manage their own affairs.

Also, why shouldn’t they be allowed to lobby in their interests? I see the need of limiting the access of lobby groups across the board and of alien influences in lobbying made visible. But again, why shouldn’t a group such as the Catholic Church with millions of members in both China and the USA not be allowed to participate in the political process, only because some amount of funding they receive or decisions they follow originate outside of these respective countries.

How does any of that relate to freedom, which should be about limiting barriers instead of raising them up, even if you dislike the outcomes that might follow?

LikeLike

Is the US “authoritarian” or “fascist” for forbidding foreign associations and corporations from making contributions to American candidates in federal, state, or local elections?

As recently as the 1960 presidential election, John F Kennedy’s Catholicism was a serious issue – not because of the American electorate’s allergic response to “freedom”, but because the Catholic Church’s dictates on many fundamental issues (including the separation of church and state) differed from what the American public agreed to in our Constitution.

Many democracies, especially those in Europe, bar certain parties from participating in the political process if they desire to overthrow the entire liberal democratic system. From Beijing’s perspective, the Vatican does not even recognize the Communist government as legitimate, regarding the regime on Taiwan instead as the true government of China. How can an organization play a constructive role in the country with such a hostile attitude?

“Freedom” can mean breaking down barriers, but never in the sense of breaking down the fence that separates your house from your neighbor’s and mowing down his lawn to your taste. The largest lobbying initiatives by the Vatican in this country have been to restrict gay men and lesbians’ freedom to marry, to restrict women’s freedom to access healthcare, and to restrict child sexual abuse victims’ freedom to access the courts. Young people are not leaving the Church in droves because they hate these “freedoms”; they are leaving precisely because they cherish them and protest the idea that the state should be the “secular arm of the Church”.

LikeLike

It’s certainly less fascist to only not allow financial contributions as opposed to simply taking over control of an organization, yes. Even though I have no doubt that the US government does what it can to control what it can not only in the USA but throughout the world. And the most recent scandal is only a reminder on how unscrupulous your government behaves at times.

Funny that you should bring up the anti catholic stereotypes against Kennedy from back in the 60s. When I brought that up years ago in a discussion about Religion in US politics, my political science professor made a remark about “nutty Americans” or something of the sort.

It’s true that many European nations forbid certain parties and movements. But even if they were right in doing so (and I don’t think they are in almost all of the cases), how big is the danger of those Catholic Chinese taking over China or posing a violent threat towards the Chinese government? I mean, you can only stretch the argument of protecting your constitution so far. If you’re a paranoid Polit-Kommissar, everyone and anything can be a threat towards the existence of the party.

With regards to your last point: So what? The US is lobbying all across the world for it’s values. Do you honestly believe that atheist groups in the US should be forbidden to work in and engage with people from other countries? I very much believe that good fences make good neighbours too, but advocating a ban on Catholic advocacy because they Church supported fascist Spain at some point and isn’t fond of gay marriage seems kind of drastic, don’t you think?

LikeLike

To answer the question of whether religious movements pose an existential threat to the Chinese government, we would have to delve into some finer theoretical points. For example, a successful Islamic secessionist movement could shatter the Communist Party’s legitimacy, as military failures abroad did in Greece and Argentina, to start a chain reaction of events that leads to the dismantlement of socialism. China’s history is riddled with examples of devastating rebellions that arose from Daoist secret societies, personal cults, and heterodox Christian sects. Ridiculing the authorities for “paranoia” is a lot easier when you don’t have access to sensitive intelligence about subversive groups’ plans for violence.

Yes, I think “atheist groups in the US should [not] be forbidden to work in and engage with people from other countries”, when the nature of this work is voluntary and charitable, rather than trying to use the coercive power of the state to enforce a particular religion’s doctrines. The “freedom not to believe” is an essential protection of secular people’s autonomy when interfacing with non-optional institutions like government and compulsory education. It’s like the right not to be punched in the face. Yes, maybe you can decry the loss of a “freedom” to punch people in the face, and maybe you think the right is not so important now, or that it’s paranoid or cute when the aggressor is not a full-grown child. But my argument is that it’s a right that people will appreciate as religious movements grow in numbers and power, which they often tend to do.

LikeLike

I have a certain sympathy for the argument that China needs to put a finger on certain religious groups or other minorities to keep the Empire together, so to speak. I’m not a liberal or a libertarian. I am not even a very good Democrat if I think about it. If I was a high ranking decision maker in China I would gladly use whatever means possible to strengthen the unity and power of my country.

However, this is probably not what you have in mind when you speak of “Freedom from Religion” as a right. Because an Islamist state like Saudi Arabia or Iran would use the same arguments to push their religious agendas.

So you are still using the language of “human rights” and “essential freedoms” while defending the methods of the police state. Because this particular police state happens to push the Agenda you’re fond of.

China doesn’t care about your freedom from religion. Just as Christian Orthodoxy has regained power since the fall of the Iron Curtain, the same could happen in China. Granted, whatever superstition would make it to the top would probably less intrusive than Islam or Christianity, but nontheless.

I don’t see constitency in your thinking. Yes, liberal democracies might eventually wither because they cannot overcome the atavistic forces of Religion and who will outbreed and outcompete open societies in the end. BUT, if you believe that, be honest about it and don’t speak of “freedoms”. What you need to keep our type of society running in the face of 100 million Mormons or Ultra Orthodox Jews or fundamentalist Muslims is not freedom but control and a strong state that is anything but democratic. Well, maybe in name only.

IMO, we are exactly heading in this direction anyways.

LikeLike

A strong state is not necessarily a police state. I’ve previously alluded to the “fortified democracy” of today’s Germany. It is a symptom of libertarian thinking that freedom from the state is conceived of as the best and truest form of freedom. I do value this sort of freedom, but oppression by religious paramilitary groups within a weak state, such as we see in many areas of the Middle East, is not ideal either.

China does care about freedom from religion. It is a basic ideological imperative to strive towards the “withering away” of religion in the final stage of communism. In fact, the imperative to “keep the Empire together” conflicts with the atheistic tendencies of the Communist Party. If you want to recruit from the impoverished, undereducated ethnic minorities of the border regions, then you can’t both categorically exclude religious people and have a healthy selection of candidates.

I don’t see the connection where “an Islamist state like Saudi Arabia or Iran would use” the “Freedom from Religion… to push their religious agendas”. I conceived of this idea precisely to stop the agendas of the likes of Saudi Arabia and Iran, whose compulsory religion is legal and unstoppable under the current human rights regime that narrowly protects the freedom of people to practice religion, and not their freedom not to practice it.

LikeLike

Love it. Very informative. I really like your analogy of religion as second hand smoke. Got to me to thinking. Its one thing to breathe ones second hand smoke. Its another to have one blow smoke in your face. Then again, I never heard anyone question one’s right to “not smoke”, which in essense is what your article addresses. The right not to believe. Therefore the right not to have smoke blown in your face without a recourse to respond. Analagous reasoning of course. Again, very informative article. Thank you!!

LikeLike

But even disregarding the user-hostile message implied in taking your life,

as even the fonts they used to call a certain process lead generation or some

amount. Flexibility of Unlimited revisions helps you to have a lot of time

to time. You face a great basis for quality or value.

LikeLike

free run nikeNiles Paul couldn’t create a spark in the kickoff return game, but put a lot of

that on the blockers in front of him. black nike free runs

cheap nike free run 2With Gay, Toronto remained a mediocre team and Gay basically got the chance to take a

lot of shots and score some points. The Raptors moved on from that failed experiment after just

51 games and Gay landed with a bottom feeder in Sacramento.Toronto got better and won the Atlantic Division for the second time in franchise history after dealing Gay but the move actually worked out well

for both parties. Gay experienced a quiet resurgence

with the Kings as he became more productive with fewer

touches, averaging 20.1 points while shooting 48.2 percent

from the field in 55 games. blue nike free runs

LikeLike